Contributed by Adam Simon / I was struck by the last two sentences of Saul Ostrow’s essay, “Painting simulacra: Brice Marden, David Reed, and Gerhard Richter.” He writes: “Marden, Reed, and Richter have sustained abstract painting’s aesthetic and cultural value as a mode of resistive thinking. In most cases, though, this has been misread or at least subsumed by its own model, thereby giving rise to the kind of acritical aestheticism and nostalgia that bolsters painters who promote gestural abstraction as a genre or motif rather than a mode of inquiry.” It took a minute to unpack this statement and allow it to sink in. Ostrow’s critique is dense, and appears to implicate most contemporary gestural abstract painters as well as contemporary criticism that dismisses the possibility of radical formalism.

Ostrow’s claim seems to be that abstract painting is inherently self-reflexive and historically aware. Forms are inherited and repurposed by each generation. Assumptions are constantly being upended, both on the part of the practitioners and of the audience. In the second paragraph, he says the works of Marden, Richter, and Reed “are a response to the intricacies of abstract painting, and highlight their audiences’ habit of seeing their expectations, rather than what is actually presented to them.” One wonders if that assessment might apply to most art viewing.

All but three (Mary Heilmann, Harriet Korman, and Eva Hesse) of the artists mentioned in the article are male. I take this as reflecting not Ostrow’s own bias but that of the historical period he is most focused on and the art market during that period. One could take the general topic of the decoupling of the painterly gesture from spontaneity, emotion, etc., and apply it, to varying degrees, to a number of female painters from a later generation. A sampling might include Jacqueline Humphries, Suzanne McClelland, Charline von Heyl, Andrea Belag, and Jill Moser. There are numerous others.

That said, it makes sense to designate Marden, Richter, and Reed as representing a shift from abstract painting as “expression of subjectivity or its reiteration of formal problems” to “the canvas’s potential as a conceptual space.” Reed is not as widely known as Marden or Richter but his representation by Gagosian, beginning in 2017 with an exhibition of his work from the 1970s curated by Katy Siegel and Christopher Wool, signals increased prominence. All three artists seem genuinely invested in the painterly gesture while remaining hyper-aware of the implications of its use. This parsing of formal decisions, where art and philosophy merge, is something Ostrow does exceptionally well. Here he situates all three painters in the context of post-Minimalism, with its rejection of both Minimalism’s formal rigor and Abstract Expressionism’s romantic and grandiose rhetoric.

None of the artists mentioned in the article show up on an internet search for post-Minimalist artists, but it’s a woefully vague category anyway and I think Ostrow’s treatment of it makes sense. I hadn’t thought about the fact that post-Minimalism was coterminous with post-Structuralism. There are key phrases in Ostrow’s text that reflect post-Structuralist language. I’m thinking of “the illusion of an impossible spontaneity,” “a simulacrum of spontaneity and process,” or “simulation of authenticity.” Ostrow refers to Richter making “representations of abstract paintings,” a mind-fuck of a phrase that warrants an article of its own. I’m reminded by all of this of one of my favorite examples of painting as a complex mode of thought: the post-Structuralist philosopher Michel Foucault’s essay on Velasquez’s painting Las Meninas, which appears in his book The Order of Things.

One could take issue with the historical specificity of Ostrow’s premise. He zones in on the brushstroke as a signifier and abstraction as a genre, but it’s possible to look at the entire history of Western painting and see assumptions constantly upended and formal propositions iconoclastically applied. Isn’t that what Manet did with the motif of the reclining nude when he painted Olympia, or what seventeenth-century Dutch painters did when they chose to focus on normal people and everyday lives? What makes Ostrow’s premise compelling is not the repurposing of the loaded brush stroke per se but the entire social and historical context in which a loaded brush came to represent authenticity and subjectivity in the first place. To cover that would require looking at the rise of the bourgeoisie leading to the primacy of the individual, the evolution of existentialism, and who knows what else.

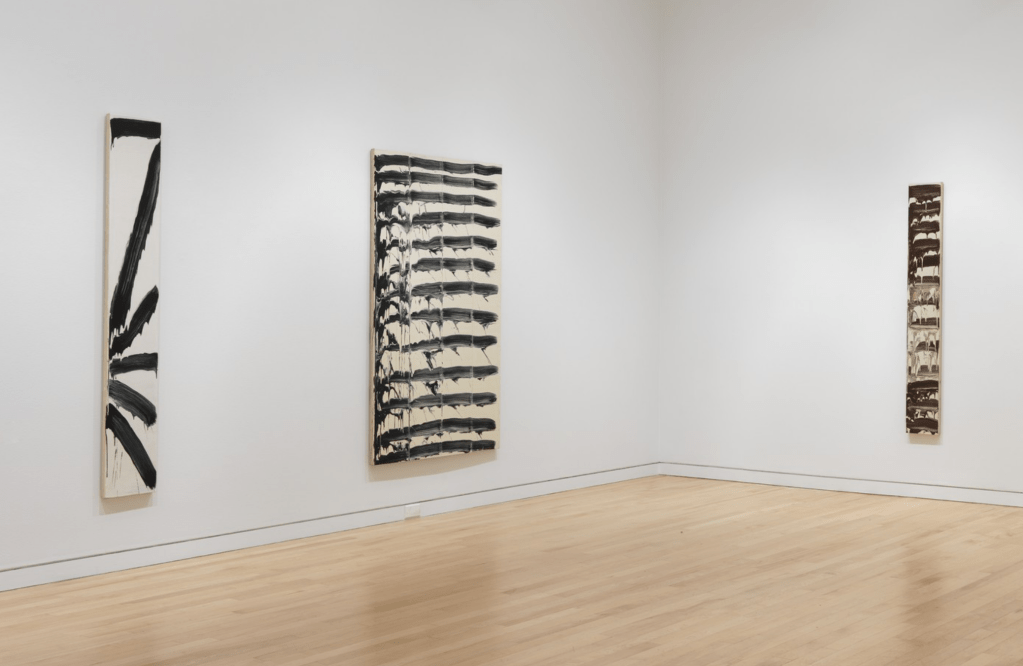

To me, the most intriguing application of the idea of painterliness as constituting something other than an indexical result of an action is to the work of Brice Marden. Even more in death than in life, Marden is seen as the Zen master of painterly abstract painting. I had never known anyone to identify artificiality in his gestures until I read Ostrow’s essay. Maybe I just need to get out more. It’s interesting, though, that what could seem to detract from the sublimity generally associated with his work in Ostrow’s essay becomes an additional way to understand his oeuvre. Rather than taking away from the “authenticity” of what Marden accomplished, Ostrow contextualizes it within the intellectual discourse of post-Structuralism. An awareness of the full, layered meaning of an action doesn’t have to diminish its effect. Art is one of the primary areas of human experience in which something can be itself and its opposite simultaneously. I see the work of these artists in that light.

Of interest:

“Harriet Korman, Portraits of Squares,” Thomas Erben Gallery, January 18 – March 2, 2024

About the Author: Adam Simon is a New York artist and writer. His recent paintings combine corporate logotypes, stock photography, and tropes of modernist design.

Thank you for an excellent, well articulated point regarding the authenticity of gestural abstraction: “An awareness of the full, layered meaning of an action doesn’t have to diminish its effect. Art is one of the primary areas of human experience in which something can be itself and its opposite simultaneously.”

Thank you Adam Simon for this clear, well defined response. As a painter whose work has addressed – gesture , albeit arrested and conscious of its time, I found myself nodding in agreement.

“…something can be its self and its opposite simultaneously…” a great point to make on the capacities of art.

Good to read this dialogue, thanks Adam and Saul.

Adam — thank you for your thoughtful and insightful response – such public critical dialogs are sorely missing –

Saul

About six paragraphs in, Adam writes about historical context and that’s what I think is the center of the target. Saul Ostrow’s article focuses on the advance of painting in the 70’s and 80’s in a way that suggests a larger backdrop.

All too often, the tales we tell of art history seem like Billy Pilgrim’s life, unstuck in time: sporadic and unchained, a knickknack drawer spilled onto the floor. Overall, there’s a general need today to make sense of the 90’s, what led up to that decade and the sense of the vaporous/vacuous decades since then, vapor in terms of the lack of coordinating theorization. In other words, today’s art world -the nascent 21st century art world- needs a description of what the hell happened in the 20th century.

I have a candidate narrative for your consideration. The very short version is about the how the burst of the Beaux Arts culminated in the triumph of Conceptualism. Out of the rupture of the Academy from the pressures of the Industrial Revolution sprung a Janus-faced Modernity, half Modern and half PostModern. The former needed a new canon and for the latter, canon formation was not only undesirable but impossible.

Whereas Modernism was driven to touch G-d via material means, PostModernism was driven to flip the script and point to the quotidian via conceptual means. In the shadow of the self extinction event of AbEx giants, Castelli’s stable of artists incubated Duchamp’s seed and Pop pointed conceptually to everyday life with abandon and subsequently the volume of materiality was dialed towards zero from Minimalism towards Conceptualism.

Sol LeWitt was the fruit of the PoMo tree and after the resultant terminal apotheosis, the complete dematerialization and the realization of art as an algorithm, art as a set of instructions, this foreshadowed the Information Age to come. Momentum was yet immense while the mass was Less than Zero. The pointing towards ordinary life via conceptual means fanned out like a great river delta meeting the sea. An immense spreading et cetera, slower and slower, stinking and fetid, evaporating to the clouds… for decades.

The only way to paint during and after the death of painting was to play dead. Play possum.

***

I remember seeing the Richter painting exhibition at MoCA/LA, when was it, in the late 80’s, yes? I forget who wrote the catalog, but the punch line was that he painted paintings that simulated photography, the necessary prophylactic making it ok to glory in lushness again without guilt. I also recall a catalog essay for Jonathan Lasker by Dr. Hans-Michael Herzog titled “Frozen Spontenaity”. My thoughts about this at the time took the form of an imagined sequel to “Night of the Living Dead” where in the opening scene, the protagonist awakens alive in a room full of Zombies. How can he get out alive (and into the coming 21st Century)?

Response to a response to a response ( a typical post-structuralist “mise en abyme”, if there is one). I’m not sure to share Dennis Hollingsworth’s pressing need for a revised narrative of the 90s. If anything, we don’t need to be told once more what art was or should be. We’ve all seen the limits of grand master narratives all too clearly. But there is indeed an underlying anxiety about the critical/theoretical vacuum we’re in, and its general sense of lack of direction, which haven’t been properly articulated yet. I suspect it might be because its messy contradictions cannot be easily resolved and cleanly packaged. (Fragments of a much longer discussion…)

Credit to Saul Ostrow for instigating this conversation and encouraging us to externalize it here in the comment section rather than nest in our inboxes. He’s right, if we lament the current state of art discourse, then we have to get involved in the public arena.

Gwenael is partly right, none of us want to be told what art should be, full stop. Short of that, is a whole wide world:

1. There’s no harm in sharing a rendition of a picture of what was, historically near or far.

2. The need to conjecture the past is an existential need.

3. Persuasion is key.

4. The problem of the abusive power of the Grand Narrative is rooted in the herd mentality. Therefore, Gwenael’s reflexive dissent is a survival instinct, bravo G.

5. Messy contradictions are inevitable for the all-too-human. Perfection exists only in heaven.

Though not always addressing art specifically, Cornelius Castoriadis has relevant thoughts on some of these issues.

Lovely thoughtful response to a thoughtful essay